Example Designer furniture

This designer chair is an example of a registered / registrable design.

Intellectual Property Principles

In the following video, Rob talks about the rights he considered to protect the IP on his safety helmet.

G'day, my name's Rob Joseph. I'm the co-founder of ANTI.I'm also a 22 year old medical engineering student in my final year here at QUT. There's a lot of opportunities in medical engineering. I really enjoy it because it's so broad and varied. I went into the degree thinking that I was going to be a prosthesis engineer for sport, but now we're designing helmets, there's a lot of sport implications as well as within hospitals and practice and helping humans to live better lives.

So ANTI is a helmet company, and we're creating the world's first truly soft, truly safe helmet, so it's more like a beanie that a hardhat, but still is as safe, if not safer than any other helmet on the market. I was snowboarding in New Zealand when I came up with the idea. So, being a Queensland boy I've always worn helmets,you know riding push bikes, motorbikes, skateboarding, wakeboarding, all those kinds of things, and always happily wore a helmet, but then I found myself in the slopes in New Zealand and I found myself really hating helmets, they were just really hard to use, really uncomfortable, and it's very frustrating, and so I took mine off, and we all know that's a stupid move. They are life-saving devices. I would never ever drive another seatbelt so while I write without a helmet? and that became very apparent to me as I hit my head on the ice going down the hill, and so I figure there has to be a better way, and we realised that most people who didn't wear helmets and even most who do, wear beanies, so we thought why can't we make it beanie that's as safe as a helmet?

The process development has been quite a long, one it's been about 18 months or so now. We started off myself and my co-founder where both have engineering backgrounds, of course I'm a medical engineering student, my co-founder is a civil engineer, so we did a lot of R&D ourselves a lot of research and figuring out what materials were going to allow us to have the flexibility and comfort that we needed in our in our helmet. So did a lot of research a lot of preliminary design ourselves. Of course a lot of the progress we've done is business development as well. Coming from an engineering background we had to learn a lot about business in the way to run, but now that we've raised a bit of money we can go through and we're working with an industrial designer is to really have our product really comfortable and in safe at the same time, so I have a really good product once we launch. The way we came up with our logo was, we knew that we wanted something short and square, and easy to read easy to put on a shirt, as well as really recognisable. We did lots of searching for our logo to make sure that we weren't infringing on anyone else's logo. We didn't want to start off a logo and have to change 12 months in. So we did a lot of looking around and just a lot of google searching and trying to find names that are similar to ours as well as logos that were quite similar as well.

One of the big obstacles we face in our business is IP. Of course because we build a physical product, and while it's quite complex and it's very new, Once we start selling, them if you get a knife and cut it open you'll see what's going on relatively easily. Anyone who knows a little bit of engineering and design will be able to figure it out. So IP is a large thing for us of course we got a lot of business development things as well. Learning very fast how to advertise and do marketing and all those sorts of things, but the IP and the engineering behind our design is one of the really big things for us.

Once we hit the market, we want to be really dominant in the snow sports industries. You know we're going to have a lot of popularity there, if the uptake is right and that's a lot of that getting a product right so people do like it at such a grassroots level, but of course it's a helmet, and the safety regulations are relatively similar between snow sports, cycling, skating and so we can branch out into those markets and with some adaptability there, we can with our ventilations and the way it sits on your head, we can really move through a lot of different markets. One that we're focusing on the moment is the epilepsy market. Currently we don't believe that kids with epilepsy are well enough catered for, in you know, for wearing helmets and so we want to branch our material out into that regard as well. When identifying which area of IP law applies to your project and your creation, a great way to figure that out is to look at what is the most exciting and innovative part of your project.

For Rob and his company ANTI, they've created a helmet that looks like a beanie. What's most exciting about that, is the way it works. When we look at how something works and that's the part we want to protect, we're looking at patent law. Patent law protects inventions. Rob also mentioned that he wanted to protect the logo of his business ANTI. Logos are protected by trademark law. For you and your project, the areas of law might be slightly different. What you need to think about is what is it that you want to protect? If you want to protect the way something looks, then you want to think about copyright and maybe design law. If you want to think about how it works, then you're looking at patent law, and if you have logos and company materials to protect then you probably need trademark law.

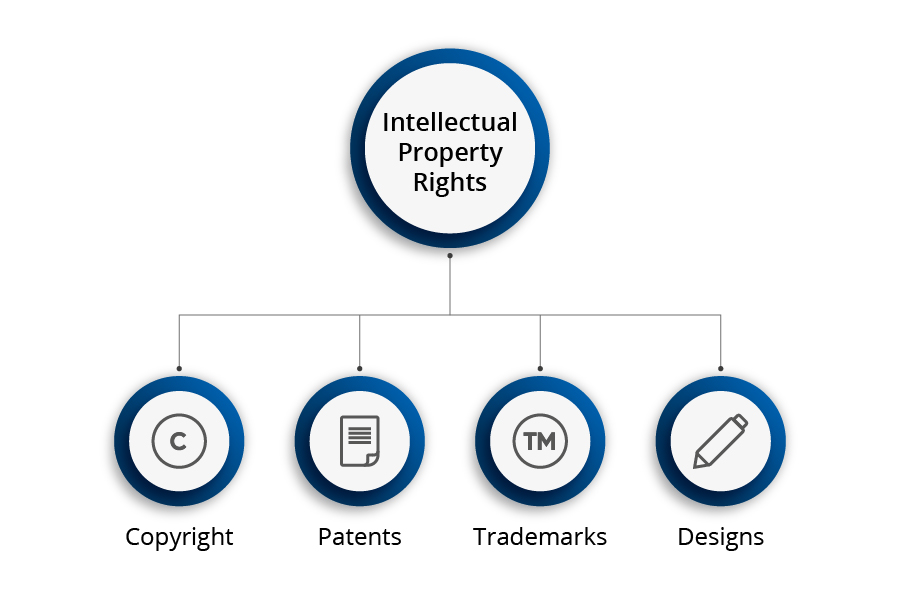

The term ‘intellectual property right’ is a broad term and branches out into different types of rights. Each of these IP rights protect different forms of intellectual property. The following diagram shows the four kinds of most widely and commonly used IP rights.

The term ‘copyright’ refers to the legal rights vested in the creators and publishers of an artistic, dramatic, musical or literary work, as well as sound recordings, films and broadcasts. From the moment a work comes into existence, copyright grants its creator an automatic right to copy, publish, perform and distribute the work.

The main objective of copyright is to promote creativity and provide incentives to people who invest their time and talent in creating works of cultural and economic significance.

Copyright protects the following types of works:

Artistic works such as paintings, drawings, photographs and sculptures

Literary works such as poems, lyrics in a song and novels

Dramatic works such as screenplays and choreography

Musical works such as musical (notational) compositions.

Copyright law does not make any judgments about the aesthetic or cultural quality of a work. Thus, a ‘literary work’ simply refers to something in writing – a book, for example, does not need to qualify as high literature to receive copyright protection. An instruction manual for a new computer may receive protection as a literary work.

Over time, copyright has evolved in its scope and application. It also covers computer programs, radio and TV broadcasts, cinematographic films (i.e. movies) and sound recordings.

A patent right is a legal right granted to protect new and useful inventions. An invention might be a product (such as a machine), a process (such as a method for extracting one chemical from another), or a new technical solution to an existing problem. Some software inventions may also be protected by a patent.

The objective of patent law is to recognise inventors for their inventions and encourage development of new technologies in every field.

A ‘trademark’, as the name suggests, is a unique mark with which a trade or business can identify itself in the market. We commonly think of these marks as ‘logos’. A trademark helps a business to distinguish its goods and/or services from competitors in a marketplace. A trademark may consist of a letter, number, word, phrase, sound, smell, shape, logo, picture, movement, aspect of packaging, or a combination of these. While it is possible to acquire a trademark over something like a colour or smell, it is extremely rare.

Once registered, a trademark gives the owner a legal right to:

The meaning and function of a ‘trademark’ is different from that of a ‘company name’, ‘business name’ and a ‘domain name’ or URL. A business may choose to adopt the same trademark as its company name, however, registering a business name or a domain name would not give the owner the right to stop others from adopting a same or similar company or business name.

Some globally recognised trademarks include the MacDonald’s golden arches, Nike, the Apple logo, and Coca-Cola.

A design right aims to protect the outward appearance or aesthetic appeal of a product. It covers shapes, ornamentation, configuration and pattern. Designs differ from patents in that they cover how a product looks, rather than how it works.

To qualify for registration, a design must have a commercial application or use, and must be new and distinctive compared to what has gone before. Once registered, the law gives the owner the sole right to commercially use, license or sell the design. Design registration lasts for 5 years, with the opportunity to renew registration up to 10 years.

For designers to get protection, a design must be registered before any manufacturing starts. One-off artistic designs for things like fashion, art, and furniture will often be automatically covered by copyright law and do not require design registration unless they are mass produced (50 or more items). Once a design is mass-produced or once the owner registers for design protection, copyright in the artist design is lost.

The on-paper designs for furniture belong to the designer, just like any other artists. But things get more complicated when designs become physical objects. Go to The Conversation to find out more.